In December 1945 an Arab peasant made an astonishing

archeological discovery in Upper Egypt.

| THE NAG HAMMADI LIBRARY / Article from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Quantum World |

last update: Sept. 14 '17 |

The Nag Hammadi Library

(now with uncensored account of the gruesome details of its discovery)

In December 1945 an Arab peasant made an astonishing

archeological discovery in Upper Egypt.

Thirty years later the discoverer himself, Muhammad 'Alí,

told what happened.

Shortly before he and his brothers avenged their father's murder in a blood feud, they had saddled their camels and gone out to the mountain to dig for a soft soil they used to fertilize their crops.

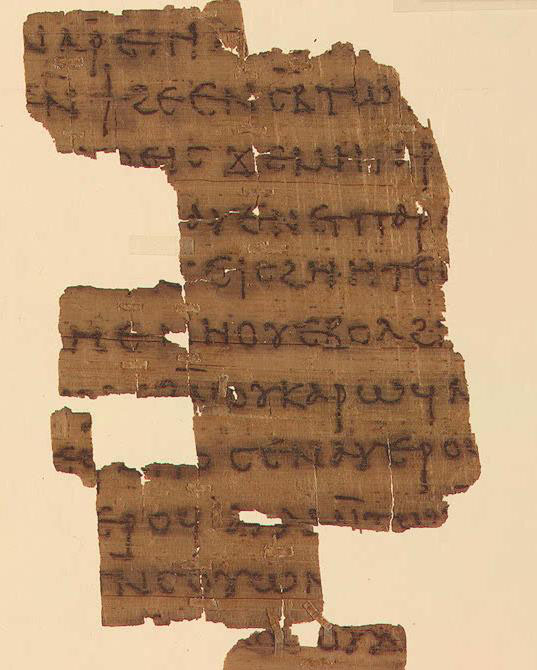

Digging around a massive boulder, they hit an almost one meter high red pottery jar.

Muhammad 'Alí hesitated to break it, fearing that a spirit or jinn might live inside.

But realizing that it might also contain gold, he raised his pickaxe,

smashed the jar, and discovered inside thirteen papyrus books, bound in leather.

Returning to his home in al-Qasr, Muhammad 'Ali dumped the books and loose papyrus leaves on the straw piled on the ground next to the oven.

Muhammad's mother, 'Umm-Ahmad, admits that she burned much of the papyrus in the oven along with the straw she used to kindle the fire.

A few weeks later Muhammad 'Alí and his brothers avenged their father's death by murdering his killer.

Their mother had instructed her sons to keep their pickaxes sharp:

when they heard that their father's killer was nearby they decided to revenge him by

"hacking off his limbs . . . ripping out his heart and eating it among them, as the ultimate act of bloody retribution."

Afraid that in the course of a murder investigation the house would be searched and the books be discovered, Muhammad 'Alí asked the coptic priest, al-Qummus Basiliyus, to hide them for him.

Whilst Muhammad 'Alí and his brothers were being interrogated for murder,

the books came to the attention of the local history teacher, Raghib who suspected that the books were of value.

The priest al-Qummus Basiliyus gave a book to Raghib who sent it to Cairo to find out its worth.

The manuscripts were then sold on the black market through antiquities dealers in Cairo.

Soon they attracted the attention of officials of the Egyptian government.

Through circumstances of high drama, a number of the leather-bound books,

called codices, were deposited in the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

But a large part of the thirteenth codex,

containing five extraordinary texts,

was smuggled out of Egypt and offered for sale in America.

Amongst them was the Gospel according to Thomas.

Word of this codex soon reached Professor Gilles Quispel,

distinguished historian of religion at Utrecht, in the Netherlands.

(Quispel urged the JUNG FOUNDATION in Zurich to buy the codex).

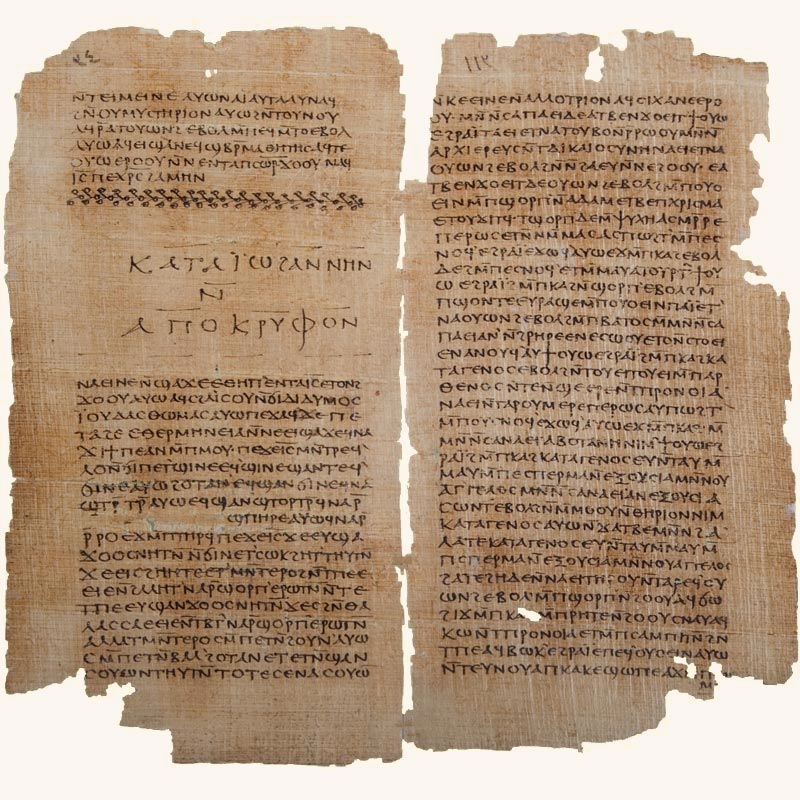

Tracing out the first line from the Gospel, Quispel was startled, then incredulous, to read:

"These are the secret words which the living Jesus spoke, and which the twin, Judas Thomas, wrote down."

Unlike the gospels of the New Testament,

this text identified itself as a secret gospel.

Quispel also discovered that it contained many sayings known from the New Testament;

but these sayings, placed in unfamiliar contexts, suggested other dimensions of meaning.

From the Gospel according to Thomas:

Jesus said,

Jesus said,

"If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you.

If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you."

Professor Helmut Koester of Harvard University has suggested that the collection of sayings in the Gospel of Thomas, although compiled 140 AD, may include some traditions even older than the gospels of the New Testament,

"possibly as early as the second half of the first century" (50-100) - as early as,

or earlier, than Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John.

Scholars investigating the Nag Hammadi find discovered that some of the texts tell the

origin of the human race in terms very different from the usual reading of Genesis.

Why were the Nag Hammadi texts buried

- and why have they remained virtually unknown for nearly 2,000 years?

Their suppression as banned documents,

and their burial on the cliff at Nag Hammadi,

it turns out, were both part of a struggle critical for the formation of early Christianity.

The Nag Hammadi texts, and others like them,

The Nag Hammadi texts, and others like them,

which circulated at the beginning of the Christian era,

were denounced as heresy by orthodox Christians in the middle of the second century.

We have long known that many early followers of Christ were condemned by other Christians as heretics,

but nearly all we knew about them came from what their opponents wrote attacking them.

But those who wrote and circulated these texts did not regard themselves as "heretics".

Most of the writings use Christian terminology,

unmistakable related to a Jewish heritage.

Many claim to offer traditions about Jesus that are secret,

hidden from "the many" who constitute what, in the second century,

came to be called the "catholic church."

The gnostic comes to understand who we were,

and what we have become;

where we were...

where we are going;

from what we are being released;

what birth is,

and what is rebirth.

To know oneself, at the deepest level,

is simultaneously to know God; this is the secret of gnosis.

Orthodox Jews and Christians insist that a chasm separates humanity from Its creator:

God is wholly other.

But some of the gnostics who wrote these gospels contradict this:

self-knowledge is knowledge of God;

the self and the divine are identical.

Jesus said,

Jesus said,

"I am not your master.

Because you have drunk,

you have become drunk from the bubbling stream which I have measured out....

He who will drink from my mouth will become as I am:

I myself shall become he,

and the things that are hidden will be revealed to him."

By A. D. 200, the situation had changed.

Christianity had become an institution headed by a three-rank hierarchy of bishops,

priests, and deacons, who understood themselves to be the guardians of the only "true faith."

If we admit that some of these fifty-two Nag-Hammadi texts represent an early form of Christian teaching,

we may have to recognize that early Christianity is far more diverse than nearly anyone expected,

before the Nag Hammadi discoveries.

Adapted from a text by:

Elaine Pagels,

an American religious historian, best known for her writing on the Gnostic Gospels.

She is the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University.

Pagel has conducted extensive research into the Pauline Epistles and the similarities between Gnosticism and Buddhism.

Her best-selling book The Gnostic Gospels (1979)

examines the divisions in the early Christian church,

and the way that women have been viewed throughout Jewish and Christian history.

Modern Library named it as one of the 100 best books of the twentieth century.

According to Pagel's interpretation of an era different from ours,

Gnosticism "attracted women because it allowed female participation in sacred rites".

From The Gnostic Gospels, by Elaine Pagels

Vintage Books, New York: 197, pp. xiii-xxiii

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/pagels.html

The Gnostic Gospels, by Elaine Pagels on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2h93mRU

Further references:

Second Treatise of the Great Seth: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Treatise_of_the_Great_Seth

The Nag Hammadi Library: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nag_Hammadi_library

Elaine Pagels: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elaine_Pagels

Photo of the Nag Hammadi Library: Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, Claremont, California.